Gumballs sure are fun, but policy decisions should be based on complete and accurate information

(For a printable pdf version please go to http://www.fishnet-usa.com/Gumballs.pdf. This should in no way be considered an attack on recreational fishuing, nor is it an attempt to in any way diminish the perceived economic importance of recreational fishing.)

Nils E. Stolpe/FishNet USA/May 9, 2014

______________________________________

Points to keep in mind while reading this:

- U.S. commercial fishermen aren’t fishing for themselves, they are fishing for the 300 million or so consumers in this country who want a diet that includes wholesome, high quality and, if possible, locally produced seafood as soon after it is caught as possible.

- The American Sportfishing Association is a trade organization that represents businesses that provide goods and services to recreational anglers. All conservation rhetoric aside, it’s members do better if there are more recreational anglers who are fishing more, and it’s no secret that getting more anglers fishing more is most easily accomplished if they are allowed to catch more fish.

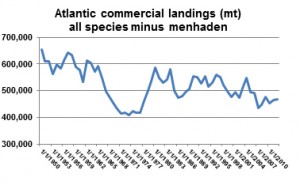

- The more fish that are allocated to recreational anglers, the less fish will be available to the non-fishing public. The rise in the consumption of cultured tilapia, cultured swai and cul-tured shrimp of questionable origin and questionable quality is due to two factors: per capita seafood consumption in the US has been tending upwards for years, and commercial landings of many of the most popular fish and shellfish produced in our exclusive economic zone have been tending down for decades (see http://www.fishnet-USa.com/After%2035%20years%20of%20NOAA.pdf and http://www.fishnet-USa.com/Research%20funding_A%20win-win.pdf).

______________________________________

The people at the American Sportfishing Association (ASA) are embarking on the second year of a campaign to convince anyone who will listen that recreational fishing is equally as or more important than commercial fishing and that in their estimation the federal government should not be putting so much emphasis on managing the commercial fisheries. It began with a press release announcing the completion of an ASA commissioned study by Southwick Associates on May 6 of last year and has progressed to a YouTube video starring gumballs as fish surrogates and with Michael Nussman, the President of the ASA, in a strong supporting role.

In the press release Nussman stated “the current federal saltwater fisheries management system has historically focused the vast majority of its resources on the commercial sector, when recreational fishing is found to have just as significant an economic impact on jobs and the nation’s economy.”

You might ask what the point of this exercise is.

According to Nussman “we’re not releasing this report in an effort to demean commercial fishing. Commercial fishing is very important to our nation’s economy! Our goal is to highlight the importance of rec-reational fishing to the nation. As our coastal populations continue to grow, along with saltwater recreational fishing, significant improvements must be made to shape the nation’s federal fisheries system in a way that recognizes and responds to the needs of the recreational fishing community.”

Among other things, “demean” means to lower in standing, and in spite of Nussman’s assurances to the contrary, it sure seems like that’s exactly what the ASA and their Southwick Associates report is attempting to do.

From the report:

“In 2011 anglers landed 204.9 million pounds of saltwater fish. In pursuit of these fish, saltwater anglers spent $26.8 billion on fishing tackle and equipment and trip-related goods and services. Including multiplier effects, their spending generated $70.3 billion in economic output (sales), created $32.5 billion in value-added growth and supported 454,542 jobs with $20.5 billion in in-come…. Of the commercial sector’s landings, 4.9 billion finfish pounds were the same species frequently targeted by anglers, with a landed value of $2.1 billion. Including multiplier effects along the entire value chain from harvesters to processors to final consumers, commercial finfish harvest of species also sought by anglers generated $20.5 billion of economic output. This is the ‘sales impact,’ which is not to be confused with expenditures or retail sales which created $10.6 billion in value-added impacts and generated 304,611 jobs with $7.5 billion of income.”

If that isn’t an attempt to lower the standing of commercial fishing, particularly when Nussman introduced the report with the words “the current federal saltwater fisheries management system has historically focused the vast majority of its resources on the commercial sector,” it’s hard to imagine what would be.

The entire report centers around the idea that expenditures on recreational fishing services, equipment and supplies are somehow equivalent – on a dollar to dollar basis – to dollars generated by commercially caught and landed finfish (The Southwick people disregard commercial shellfish landings, which will be discussed below).

In reality commercial fishermen and the people in every other business in the seafood supply chain are dedicated to producing the best possible product at the lowest possible price, as are any business owners engaged in producing products in a free market system. If they weren’t they wouldn’t be in business for very long, because there is a world’s worth of alternative center of the plate proteins competing for the US consumers’ dollars. On the other hand recreational fishermen aren’t buying fish when they go fishing, they are buying a recreational fishing experience, and the more pleasurable that experience is the more they are likely to spend. Within limits this isn’t determined by the amount of fish caught. Recreational fishermen aren’t driven by anything approaching the bottom-line constraints that commercial fishermen and others in the seafood supply chain face.

To equate what a recreational fisherman pays to catch a fish to what a commercial fisherman is paid to catch that same fish is to equate the total cost an equestrian pays to ride her horse for a mile to what Amtrak would charge to move her the same distance on a train. Apples and oranges doesn’t come close to describing how unapt the Southwick comparison is, maybe Ferraris and oranges does.

Why omit shellfish?

In the Southwick report the authors also ignore the value and the economic contributions of the commercial shellfish fisheries (mollusks and crustaceans), stating as their rationale “shellfish are rarely targeted by anglers.” This implies that there is no relationship between commercial shellfish fisheries and commercial or recreational finfish fisheries. The impact that the yellowtail flounder fisheries have on the New England/Mid-Atlantic sea scallop fishery, the most valuable commercial fishery in the US, demonstrates how a seemingly unrelated fishery can have a profound effect on another, and how “dismissing” any of our fisheries, recreational or commercial, can leave naïve readers with severely distorted impressions.

The New England/Mid-Atlantic sea scallop fishery is constrained more by the catch of yellowtail flounder, which supports a small recreational fishery in New England, than it is by sea scallop abundance. If the small allocation of yellowtail flounder is inadvertently exceeded by the sea scallop fleet the sea scallop fishery will be closed for a predetermined period in the subsequent fishing year depending on the amount by which the allocation is exceeded. The allocation of yellowtail flounder to the scallop fleet has been on the order of 500 metric tons annually. The sea scallop fishery, the most valuable commercial fishery in the US with landings that have averaged over a half a billion dollars a year in recent years, is dependent on catching just over a million dollars’ worth of these flounder (that have an ex-vessel value of around a dollar a pound). If the yellowtail flounder population declines for any reason the allocation of them to the sea scallop fishery will be reduced proportionally, as will the sea scallop catch.

The Gulf of Mexico/South Atlantic shrimp fisheries provide another example of how closely intertwined commercial shellfish fisheries and commercial/recreational finfish fisheries are. Domestic shrimp fisher-men exert a tremendous effort – at a tremendous expense – to avoid bycatch of juvenile stages of important finfish species, particularly snapper and grouper. The Mid-Atlantic/New England squid fishery is managed in large part for the butterfish bycatch (more on butterfish later). And there are similar finfish interactions in other shellfish fisheries.

Also, and it’s kind of surprising that the Southwick people ignored this, a small yet significant part of the “commercial” shellfish harvest goes to providing bait to recreational anglers, and the price that they pay for their clams, shrimp, squid and clams tend to be quite a bit higher than what consumers are willing to pay for the same products at the seafood counter.

In ignoring the value of the commercial shellfish fisheries the report makes it appear as if fish caught by recreational fishermen add three times as much value to the economy as fish caught by commercial fishermen. The inclusion of all commercially caught fish and shellfish would definitely affect this ratio, meaningless as it is. In fact, well over half of the commercial finfish catch is composed of relatively low value per pound species and virtually all of the commercially caught shellfish are high value per pound. In 2012 the ten most valuable commercial finfish species had an average landed value of less than 26 cents per pound while the ten most valuable shellfish species had an average landed value of over two dollars per pound.

No matter what the reasoning, not considering the entire commercial fishery relative to the entire recreational fishery leaves readers with an incomplete and very possibly distorted picture.

What about exceeded quotas?

In every discussion about inequities in recreational fisheries management this seems to be the 800 pound gorilla lurking invisibly in the corner.

If you are at all familiar with the current state of fisheries management in the US you know that it’s next to impossible for commercial fishermen to overfish their quota (or TAC or whatever it’s called) in federal waters. Unfortunately that’s not the case with recreational fishermen in recreational fisheries or in those that they share with their commercial colleagues.

At this point virtually every commercial fishery that takes place in federal waters is under one form of limited entry or another. What this means is that you need a federal permit to participate in those fisheries. The number of permits allowed in each fishery is limited. Accordingly it takes more than a boat and a desire to participate in a particular fishery to fish. The controls on the limited number of commercial fishermen in a particular fishery can (and usually do) limit where they can fish, when they can fish, how they can fish, the size and horsepower of their boat, the type and amount of gear they can use and the size and amount of the fish they can catch. Depending on the fishery, when a predetermined amount of a particular species is caught the fishery may be shut down. If the amount caught exceeds the commercial quota, as with yellowtail flounder in the sea scallop fishery, the excess amount may be deducted from the following year’s quota.

Recreational fishermen are managed with various combinations of size, season and bag limits (the number of a particular species of fish that they can have in possession). However, there is no limit to the number of fishermen who can participate in a recreational fishery, nor in how many trips they may make in which they catch a particular species. It seems obvious that a fisheries management system that for all intents and purposes has no cap on the number of participants nor on the number of fish of a particular species each of those participants can take can be pretty far from effective. Recognizing this and effectively dealing with it is one of the improvements that is definitely necessary to, in Mr. Nussman’s words, “reshape the nation’s federal fisheries system.”

As the chart below (from NOAA/NMFS) shows, the number of saltwater recreational anglers, which remained reasonably stable for the last two decades of the twentieth century, grew significantly in most of the first decade of the twenty-first, until the “Great Recession” began. Whether most of those who left come back to the sport or not, there are and will continue to be millions more than there were a decade ago while the productive capacity of our waters isn’t going to increase significantly.

What of what seems to be an underlying theme of Mr. Nussman’s remarks in the press release and in his gumball presentation; the idea that the commercial fisheries are making off with most of the fish and that’s costing the US economy billions of dollars? Coincidentally NOAA/NMFS in the 2012 edition of Fisheries of the United States included a graph titled Top Ten Recreational Species-Harvest Vs. Commercial Harvest reproduced below.

With the exception of Atlantic cod and summer flounder, well over half of the harvest of each of the most recreationally sought species nationally are taken by recreational anglers (I’ll note here that the commercial Atlantic cod fishery was historically our most significant commercial fishery since well before the founding of the United States and the summer flounder fishery has been one of the most important commercial fisheries in the Mid-Atlantic for most of the last hundred years).

Could it be that Mr. Nussman wants even more of these and other species to meet what from a management perspective appears to be the uncontrollable demands (by managing what an angler can catch per trip but not the number of anglers/number of trips) of the recreational anglers? The commercial landings of these ten species and any others that support both recreational and commercial fisheries seem meager indeed, particularly when one considers commercial landings in the US in their entirety. But they certainly aren’t to the fishermen, recreational, party/charter and commercial, who catch them and the businesses they support. And, while Mr. Nussman lumped all commercial finfish fishermen and fisheries together, that is certainly not the real world case. The most valuable commercial fisheries generally involve large companies, big boats, a lot of onshore or onboard processing and a lot of capital. The smaller ones generally don’t, and in them are the fishermen who would suffer the greatest harm from any reallocation. They are also the fishermen who have been the bedrock of our fishing communities from Maine to Alaska and beyond, and as we’re already seeing, as we lose them we lose those communities as well.

The final chart, again from NOAA/NMFS, shows how the number of fish taken home by saltwater anglers each year has declined to less than half of what it was in the 1980s. While I’m in no way expert on the saltwater recreational angling industry, this seems to be a pretty unsustainable trend, but does its continuation have to be inevitable? No more inevitable than the constant whittling down of commercial and recreational quotas are.

Is there a solution to what I’ll call the saltwater recreational anglers’ dilemma?

Every year more commercial fishermen and the people in fishing dependent businesses are realizing that better science almost always means more fish – and when it doesn’t we definitely don’t want to be catching too many. As long as the precautionary principle is applied only to protect the fish and not to protect fishing communities and is rigidly controlling fisheries management decisions, what we don’t know about fish stocks is going to hurt us. Some of us have come to terms with this and are committing to collaboration with researchers ashore and on the water. One of the most recent positive results of this was announced by the Mid-Atlantic Council last week, reporting that a just completed stock assessment determined that butterfish were presently not overfished and hadn’t been for at least twenty-three years. This assessment was the result of several years of cooperation and collaboration between the Council staff, researchers at the Northeast Fisheries Science Center and several universities, fishermen and their representatives. It wasn’t easy, but it’s getting easier, and the reward is going to be larger – but sustainable – harvests of both butterfish and squid. And it didn’t involve any fishermen trying to grab quota from any other fisherman. All it involved was getting the science closer to right.

A recent NOAA/NMFS publication (Fish Assessment Report – Fiscal Year 2014 Quarter 2 Update available at http://www.st.nmfs.noaa.gov/Assets/stock/documents/report/FY14Q1_AsmtReport_Summary.pdf) reported that only 59.6% of the fish stocks listed on that agency’s Fish Stock Sustainability index had “adequate” assessments (from NOAA/NMFS “generally a minimally adequate assessment can be con-ducted where there is good information on the level of annual catch and an indicator of the degree of change in stock abundance over time”). Over 40% of our important fish stocks do not. What that means is that, because of the precautionary principle the harvest of almost half of our important fish stocks are too low because we don’t know enough about them because the science isn’t there to adequately assess them.

There’s definitely a message in there for Mr. Nussman and his members. And it wouldn’t require gumballs to illustrate it.

I would be remiss if I didn’t finish this with a reminder that we are importing on the order of 90% of the seafood we consume in the U.S. and fresh, locally produced fish is getting harder and harder to find and increasingly expensive. There are more fish out there. We need to find or force the funding to provide our scientists and our managers with the science necessary to adequately manage our fisheries. That would be good for everyone, not just the recreational fishermen, the commercial fishermen or the party/charter fishermen.